Uganda’s DEI Biopharma gene therapy breakthrough could transform sickle cell treatment

Invented by Matthias Magoola, the platform targets a universal genetic switch to enable scalable gene therapy

Ugandan biotechnology company DEI Biopharma has announced a scientific breakthrough that could significantly reshape the treatment of sickle cell disease, offering new hope to millions of patients worldwide—most of whom live in Africa.

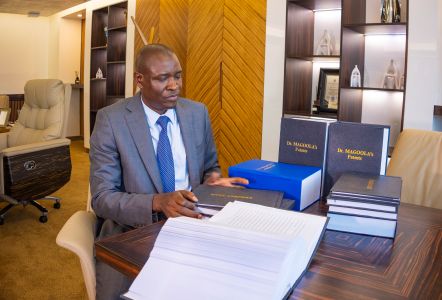

The Matugga-headquartered global biotech firm says it has developed a gene therapy platform capable of making curative treatment for sickle cell disease far more affordable and accessible than existing options. The innovation, invented by the company’s founder and chief executive Matthias Magoola, has been accepted for patenting by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).

Sickle cell disease is an inherited blood disorder in which red blood cells become warped, leading to severe pain, infections, organ damage, and reduced life expectancy. While recent advances in gene therapy have shown the disease can be cured, the extremely high cost—often running into millions of dollars per patient—has placed these treatments beyond the reach of most people, particularly in low- and middle-income countries such as Uganda.

DEI Biopharma’s approach seeks to address not only the biological basis of the disease, but also the long-standing access barriers that have defined sickle cell care.

All humans are born producing foetal haemoglobin, an oxygen-carrying protein present during pregnancy and early infancy that protects red blood cells from sickling. Foetal haemoglobin production continues from early pregnancy until about six months after birth, after which the body naturally switches to adult haemoglobin.

In people with sickle cell disease, symptoms usually begin when this genetic switch malfunctions, allowing defective adult haemoglobin to replace the protective foetal form.

Rather than attempting to repair the faulty gene in each patient, DEI Biopharma’s scientists have developed a way to keep foetal haemoglobin production switched on.

Using CRISPR gene-editing technology, the platform targets a genetic “control switch” that regulates the transition from foetal to adult haemoglobin. By disabling this switch, the body continues producing the protective foetal form, preventing red blood cells from becoming rigid and distorted.

Using CRISPR gene-editing technology, the platform targets a genetic “control switch” that regulates the transition from foetal to adult haemoglobin. By disabling this switch, the body continues producing the protective foetal form, preventing red blood cells from becoming rigid and distorted.

Crucially, because this genetic switch is shared by all humans, the treatment can be standardised rather than customised for individual patients.

“This invention was designed from the beginning to solve not only the biology of sickle cell disease, but also the access problem,” Magoola said. “By targeting a universal genetic switch rather than the sickle mutation itself, we can develop a single, standardised treatment that works for all patients.”

Current curative approaches for sickle cell disease often rely on bone marrow transplants or highly personalised gene therapies that require donor matching, complex laboratory processes, and specialised medical facilities—requirements that make them impractical in most countries where the disease burden is highest.

DEI Biopharma says its platform removes many of these barriers. The same gene-editing product could be manufactured at scale, stored, distributed, and administered across diverse populations and health systems.

The company estimates that the approach could reduce the cost of gene therapy for sickle cell disease by more than 95 percent, potentially placing curative treatment within reach of public health systems in Africa, the Middle East, and parts of Asia.

By focusing on a shared genetic mechanism, the therapy could be applied across all major forms of the disease, including HbSS, HbSC, and sickle beta-thalassemia.

“This opens the door to what could become the first scalable, broadly applicable gene therapy for a single-gene disease,” Magoola said.

Sickle cell disease affects an estimated 20 million people globally, with the vast majority living in sub-Saharan Africa. Yet most advanced treatments have historically been developed for high-income markets, reinforcing global health inequalities.

DEI Biopharma describes its innovation as a new model for gene therapy, borrowing from the logic of generic medicines—where standardised products enable scale, lower costs, and wider access once regulatory approvals are secured.

“Sickle cell disease disproportionately affects populations that have historically been last to benefit from medical innovation,” Magoola said. “Our objective is to reverse that pattern by making advanced gene therapies manufacturable and affordable at global scale.”

The patent covers the gene-editing tools, delivery methods, and therapeutic processes required to activate fetal haemoglobin. The company is currently conducting preclinical studies to assess safety, durability, and effectiveness ahead of human clinical trials.

DEI Biopharma says it plans to work closely with regulators, research institutions, and strategic partners as it advances the platform toward clinical development.

For Magoola, the breakthrough reflects a broader ambition to ensure that cutting-edge biological medicines are not reserved for a small share of the world’s population.

“Our commitment has always been to make advanced biological drugs accessible to the more than 90 percent of people who currently cannot afford them,” he said. “This innovation brings that goal closer to reality.”

Government reaffirms commitment to capitalise UDB as Bank deepens development finance role

Government reaffirms commitment to capitalise UDB as Bank deepens development finance role

Equity Bank Uganda set to close 2025 on firmer footing as clean-up phase gives way to growth

Equity Bank Uganda set to close 2025 on firmer footing as clean-up phase gives way to growth

Stanbic targets wider access to affordable financing with ‘Oli In Charge’ campaign

Stanbic targets wider access to affordable financing with ‘Oli In Charge’ campaign

USA–Canada certification dispute could expose Uganda and regional airlines to regulatory risk

USA–Canada certification dispute could expose Uganda and regional airlines to regulatory risk

Sumsub launches AI Agent Verification as Africa grapples with surge in AI-driven fraud

Sumsub launches AI Agent Verification as Africa grapples with surge in AI-driven fraud

KPMG flags widening execution gap as tech leaders bet on AI maturity, talent and partnerships

KPMG flags widening execution gap as tech leaders bet on AI maturity, talent and partnerships