New study finds elevated fish disease risk in Lake Victoria’s cage farming sector

A groundbreaking study has raised the alarm over rising disease outbreaks and antimicrobial resistance in Lake Victoria’s rapidly expanding cage aquaculture industry, with implications for food security, farmer incomes, and regional trade.

The three-year research effort, conducted jointly by Cornell University, the Kenya Marine Fisheries Research Institute (KMFRI), and the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), reveals that more than 80 large-scale tilapia mortality events were recorded between 2020 and 2023, wiping out over 1.8 million fish. However, less than 40pc of these incidents were formally reported, and only a fraction of farmers sought professional treatment.

“This is the first known study in Lake Victoria to isolate and identify bacterial pathogens from a mass mortality event and to test their resistance to antibiotics,” said Eric Teplitz, lead author and veterinarian at Cornell University. “We found a range of opportunistic bacteria often triggered by environmental stressors like poor water quality and overcrowding.”

The research team’s findings highlight deep-rooted challenges in fish health management and point to inadequate disease monitoring, poor cage management practices, and insufficient biosecurity. At the heart of the crisis is a fragile diagnostic system—one that leaves farmers to rely on guesswork and sometimes indiscriminate antibiotic use, further compounding the problem of antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Ekta Patel, an AMR expert with CGIAR and ILRI, emphasized that aquatic ecosystems remain largely overlooked in the fight against AMR. “Antimicrobial resistance is not just a human health issue,” she said. “It is a growing food systems challenge that demands better surveillance and more robust diagnostics.”

The study proposes proper disposal of dead fish through composting or burial, siting cages in deeper, better-oxygenated water, avoiding overcrowding and poor water circulation due to clogged nets, and early recognition and reporting of disease to relevant authorities, as practical solutions that could mitigate the growing threat.

Supported by farmer workshops and disease surveillance activities in Kenya’s Kisumu and Busia counties, the initiative also represents a broader push to align aquaculture practices with One Health principles—bridging environmental, animal, and human health priorities.

Christopher Aura, Director of Freshwater Systems Research at KMFRI, described the research as a model for how locally rooted science can shape national aquaculture policy. “We now need better systems for data sharing and coordination between farmers, regulators, and research bodies,” he noted.

The researchers are calling for an integrated, regional approach to aquaculture development that addresses biosecurity gaps, invests in fish health systems, and supports evidence-based regulation of antimicrobial use.

Kathryn Fiorella, the study’s principal investigator from Cornell, said the industry’s future hinges on smarter disease management. “Aquaculture can deliver jobs and nutrition, but only if we manage disease proactively. Strengthening diagnostics and engaging with farmers are essential steps toward sustainable growth.”

Lake Victoria’s cage aquaculture industry—spread across Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania—has seen accelerated investment over the past decade. However, as this study warns, unchecked biological threats could undermine the sector’s promise unless action is taken now.

Uganda’s DEI Biopharma gene therapy breakthrough could transform sickle cell treatment

Uganda’s DEI Biopharma gene therapy breakthrough could transform sickle cell treatment

KPMG flags widening execution gap as tech leaders bet on AI maturity, talent and partnerships

KPMG flags widening execution gap as tech leaders bet on AI maturity, talent and partnerships

Uganda targets 200,000 visitors for 2026 National Agricultural Show in Jinja

Uganda targets 200,000 visitors for 2026 National Agricultural Show in Jinja

Uganda coffee earnings hit record UGX 8.8 trillion as export volumes surge

Uganda coffee earnings hit record UGX 8.8 trillion as export volumes surge

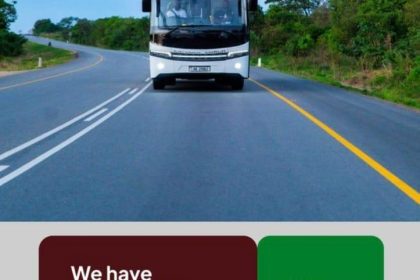

Kiira Motors’ Pearl to Cape Expedition delivers 820-bus order pipeline, recasting Africa’s electric mobility narrative

Kiira Motors’ Pearl to Cape Expedition delivers 820-bus order pipeline, recasting Africa’s electric mobility narrative

Pearl to Cape electric expedition crosses 81pc mark as Kayoola E-Coach delivers hard performance data

Pearl to Cape electric expedition crosses 81pc mark as Kayoola E-Coach delivers hard performance data